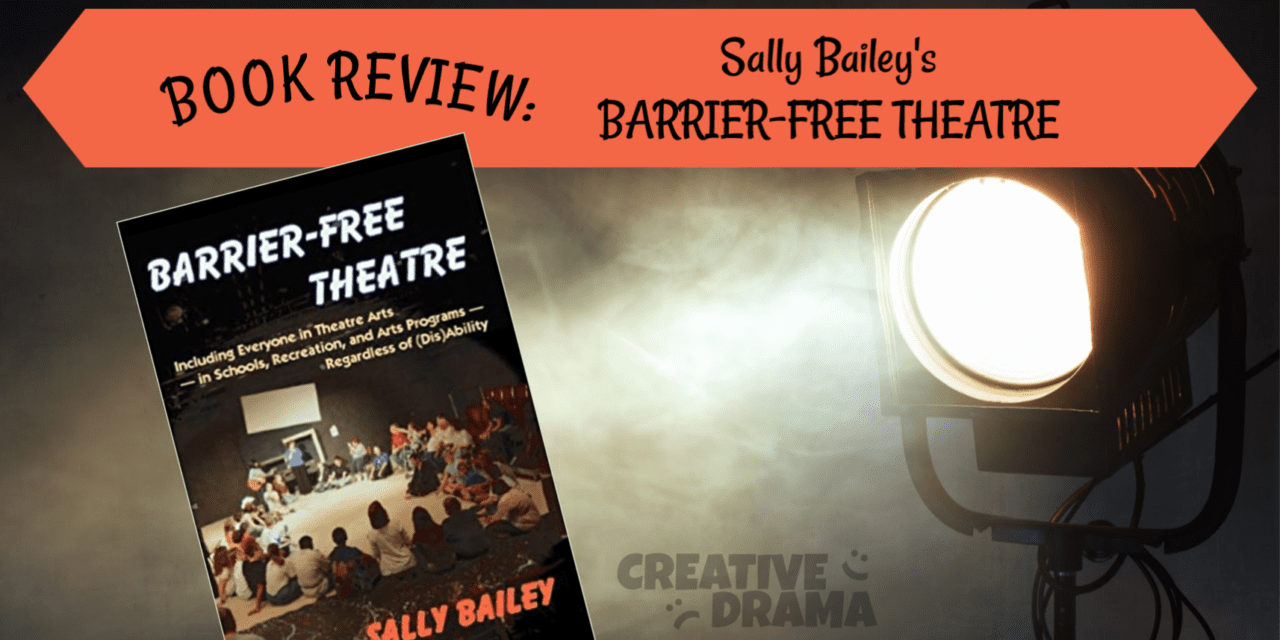

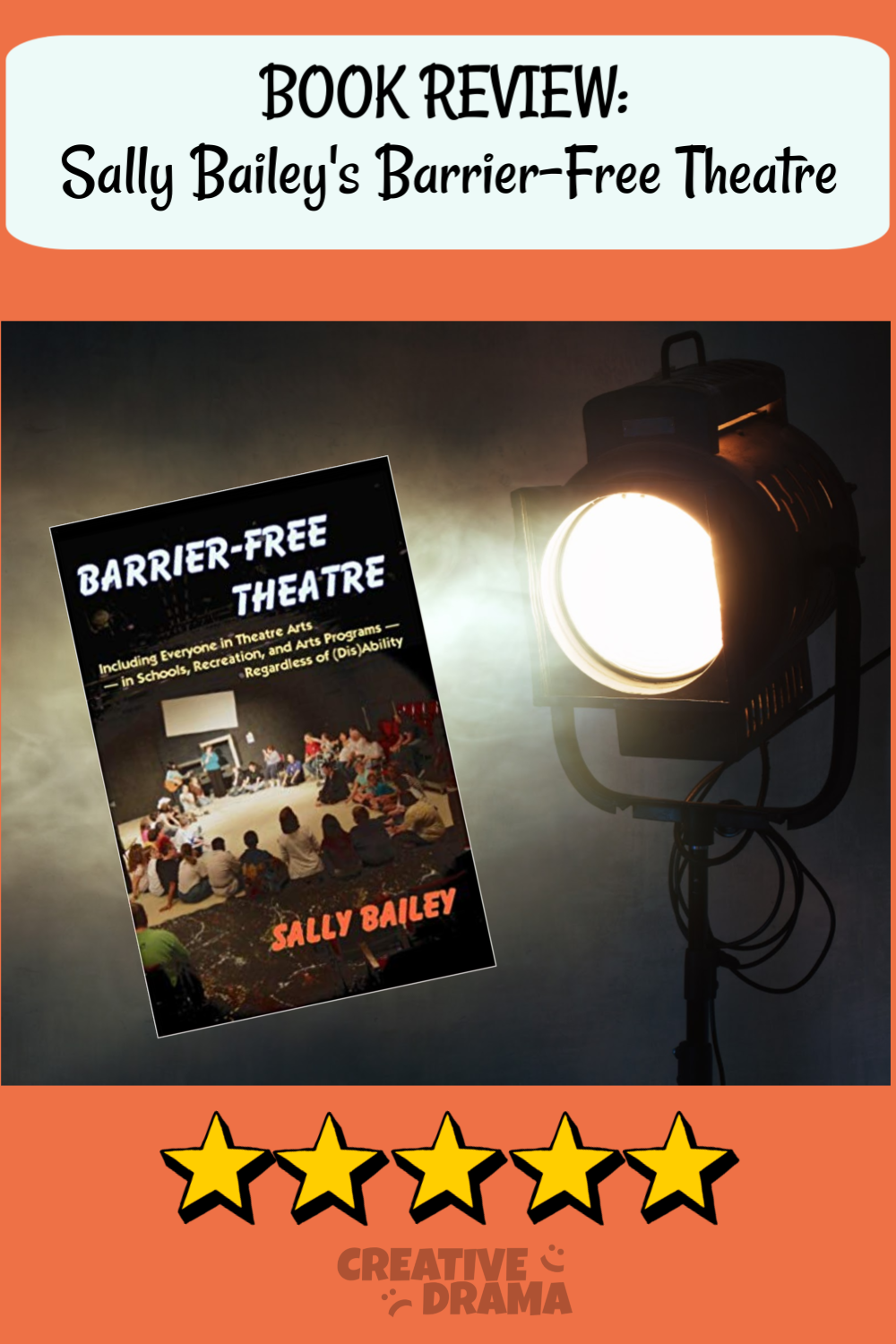

Barrier-Free Theatre: Including Everyone in Theatre Arts – in Schools, Recreation, and Arts Programs – Regardless of (Dis)Ability

By Sally Bailey

A few years out of college, I came across a book titled Wings to Fly: Bringing Theatre Arts to Students with Special Needs. The author was a teacher at the Bethesda Academy of Performing Arts, an extracurricular arts school not far from my alma mater. (N.B. Bethesda Academy of Performing Arts is now Imagination Stage.) I had had some exposure to special education topics in undergrad, but no practical classroom experience. Wings to Fly explained in detail the challenges of different disabilities and gave practical techniques for working with students in self-contained and mainstreamed situations. It was a terrific book, and I was shortly able to use some of Bailey’s games and techniques with a class of cognitively disabled young adults (my school called the class Life Skills). I praised the book for helping me so much that their classroom teacher asked to borrow it… and I failed to make sure it was returned.

And then, the book was out of print.

Wisdom Tidbit: Put bookplates in your books!

Recently, my sister was able to find a used copy of the book, and gifted it to me, along with Sally Bailey’s new book, Barrier-Free Theater: Including Everyone in Theatre Arts – in Schools, Recreation, and Arts Programs – Regardless of (Dis)Ability.

I discovered that Bailey integrated nearly ALL of the content from Wings to Fly into Barrier-Free Theater. Moreover, Bailey has added a LOT more content, and it’s updated with resources, recent legal information, and feedback from students and their parents.

Bailey also provides a lot of anecdotes from her classroom and supervisory experiences and includes some from teachers who have worked with her.

Introduction, Chapters 1 & 2

In the Introduction, Bailey tells the story of how she “Learned to Make the Arts Accessible,” and it’s an inspiring narrative. Chapter 1 covers “The Need for the Arts” in general. Chapter 2, “Disability and the Arts,” addresses the skills that drama can help develop in participants with disabilities as well as the stigma that persists against persons with disabilities. Reading through the chapter, I noted that the skills Bailey listed were ones that theatre can build in ALL participants, but she details how dramatic activity can specifically assist with individual challenges.

The section on “Dealing with Stigma” is a clear and concise explanation of cultural and historical factors that resulted in people with disabilities being labeled and ostracized as “other.” Her objective is to get the reader to understand that “the ideal response is to genuinely value people who are different…If you do not respond (to clients/students/actors) with valuing, you need to work on making the shift to it in your heart and mind.”

Chapter 3: Physical Disabilities

Bailey recognizes that some of the information she provides will be familiar to different segments of her audience. Special Education teachers might be tempted to skip Chapter 3: Physical Disabilities or Chapter 4: Cognitive Disabilities, but Bailey packs so many drama class tidbits in her explanations of the different disabilities, it’s worth reading even if some of the material is review. Likewise, she sometimes signals the non-theatre artists that she’s about to explain basic stage terminology, but she integrates these terms and concepts with applications for participants with disabilities.

Bailey starts with the reader’s physical plant – the places where participants will be learning and performing – and how you can make sure it’s accessible. She includes great informational resources listed in the “Accessible Buildings” section of the chapter, and Bailey even makes suggestions for funding improvements to spaces. If you’re looking to make an arts space ADA-compliant or improve an ADA-complaint space into one that is truly accessible and equitable, Barrier-Free Theatre provides detailed information on ADA requirements, and a checklist for buildings, classrooms and performance spaces.

The rest of Chapter 3 details orthopedic disabilities, spina bifida, cerebral palsy, osteogenesis imperfecta, diabetes, visual impairments, and deafness. Bailey provides clear information for teacher/directors for each type of disability. Since the likelihood is small that any reader has had students with all of the disability, it makes the ideas accessible for beginning teachers as well as experienced ones. Bailey details inclusive methods for all, both from a teaching perspective and a humanistic one.

Most importantly, Bailey reminds teachers to…

Chapter 4: Cognitive Disabilities

“No one has a perfect brain”

In Chapter 4: Cognitive Disabilities, Bailey continues to emphasize the uniqueness of individuals; even though the people who have the same cognitive disability share “similarities in processing disturbances,” functioning can vary “greatly from one individual to another.”

Bailey covers a wide variety of cognitive disabilities: learning disabilities such as dyslexia and sensory integration disorder, speech and language disorders, ADHD, epilepsy, traumatic brain injuries, and Tourette’s Syndrome in the first part of the chapter. She delivers an overview of each type, and then gives practical suggestions for adapting theatre work with students who have the disability.

Bailey separates Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities into their own section; here she covers students with fetal alcohol syndrome, PKU, lead poisoning, Down Syndrome, and Williams Syndrome. Bailey discusses IDD in generalizations to start, then delves into the specific diagnoses of Williams Syndrome and Down Syndrome. She presents lots of “good-to-know” facts that may affect individuals in a theatre classroom, but is careful to point out that there are moments when the exception to the “rule” shows up.

The final section of Chapter 4 is Autism Spectrum Disorders: Autism, Asperger Syndrome, and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. (N.B., Barrier-Free Theatre has a copyright of 2010, prior to the removal of Asperger Syndrome from the 2013 DSM-5 as a distinct diagnosis.) Bailey includes strategies to help a teacher help students with autism succeed in a theatre classroom.

Chapter 5: Getting Off to A Good Start: Basic Adaptations for the Drama Classroom

In Chapter 5, Bailey covers how to make sure your classroom space is suitable for drama activity: size, acoustics, lighting, and lack of distractions (note: the physical therapy room filled with apparatuses is not a good choice). She emphasizes the importance of class assistants (as separate from one-on-one aides that students may need) and what qualities they should have. According to Bailey, the most important prerequisite to taking a drama class is the student’s desire to TAKE A DRAMA CLASS. If the desire’s not there, it’s unlikely that the student will have a successful experience. Bailey offers some guidelines for placing students and details a Deaf Access Program she developed while at Bethesda Academy for the Performing Arts. In addition to a discussion of class size and culture, there’s are in-depth suggestions for classroom management when you’re working with a group of “all abilities” students.

Chapter 6: Creative Drama and Improvisational Acting Classes: Further Adaptations for the Drama Classroom

Chapters 6 through 10 have material in them that many theatre teachers will find familiar. Bailey’s section on Creative Drama is an excellent overview of the process. She specifies how a teacher might give directions differently to a group that includes students with cognitive disabilities:

“Illustrate (each step) through as many different sensory channels as you can.” (187)

“Allow processing time” (187)

Bailey provides a list of actor guidelines – for example, making sure everyone is clear on the difference between pretend and real – as well as audience rules for creative drama.

The only quibble I have with Bailey’s creative drama recommendations is her insistence that telling a story is always superior to reading it. I believe that the use of books in a creative drama classroom communicates the importance and excitement of reading to students in a way that they might not experience in a “typical” language arts classroom. This discovery can be particularly significant to struggling readers.

The section on conducting an improvisation class provides valuable suggestions on side-coaching and dealing with reluctant actors.

Chapter 7: Lesson Plans and Activities that Work

Bailey has a variety of warm-ups, movement, and sensory activities in Chapter 7. I have done many of these activities with students, and they are great for a wide variety of ages and abilities. One of the more unusual sections for a theatre education book is Bailey’s suggestions of art activities, which include prop construction and mask-making.

Chapter 8: Puppetry

Bailey recommends puppetry as a class for students with all abilities because it has a clear, concrete goal, a built-in delineation between the performer (puppeteer) and the character she’s portraying, and a way to “hide” for a shyer student.

Chapter 9: Developing Original Scripts for Performance

“It is essential for novice performers to experience success.”

The advantages to devised theatre are particularly poignant for students with disabilities. You can, write a piece that’s custom-made for the cast’s strengths, using with their own input. Having the cast involved in their own script development makes for a higher-level learning experience, which most educational communities strive to give all of their students.

Bailey does a fantastic job addressing educators’ misapprehensions about creating original work; giving a clear outline of the steps to developing a script; incorporating art, music, and dance; and making adaptations as needed for actors.

Chapter 10: The Rehearsal Process

While the information Bailey provides in Chapter 10 regarding the scheduling and conducting of rehearsals is incredibly useful, my favorite parts of this section were the anecdotes written by participants, parents and teachers who experienced and witnessed the magic of theatre.

Chapter 11: Drama as a Classroom Teaching Tool

This chapter covers using drama in arts-integrated lessons as a way for students to learn “typical” curriculum material such as science, language arts, or social studies. Bailey also shows how drama can be used effectively to teach “life skills” to students with developmental disabilities. Some of the skills students learn are eating out at a restaurant, going shopping, or just meeting a new person. Improvising these situations with students role-playing the various people involved in the social transactions is a good way to get students ready for a real-life experience.

Chapter 12: Inclusion

“Making accommodations for students with disabilities also means making sure typically developing students are ready to welcome them into class.”

Bailey’s experience as the Arts Access Director for BAPA is invaluable in Chapter 12. She knows what steps to take in advance of inclusion, and has seen the results of mistakes made by teachers and administrators when they didn’t “buy into” the program.

Conclusion:

Bailey has “Recommended Reading” sections at the end of each chapter, and these are all compiled into a “References” list at the end of book. There’s a comprehensive Index as well; something I wish EVERY theatre education book had!

I wholeheartedly recommend Barrier-Free Theatre: Including Everyone in Theatre Arts – in Schools, Recreation, and Arts Programs – Regardless of (Dis)Ability. It’s a must-have book for teachers, artists, administrators, therapists, and recreation directors who serve (or aspire to serve) diverse populations.