Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children by Geraldine Brain Siks

Have you ever wanted to teach in a Theatre Education Utopia? In Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children, Geraldine Brain Siks seems to be doing so!

After reading Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children, I was left wondering what it must have been like to be Siks, teaching in the Seattle area, in the 1950s. I imagine it was a bit like Pleasantville…before Reese Witherspoon and Toby Macguire’s characters started messing with the fictional universe. The students Siks describes are, with few exceptions, heterogeneous – same race, culture, and religion. They are similar in obedience – no one has behavioral difficulties that compare to what most teachers face in their classrooms today – as well as in cleanliness and engagement in the activities.

Geraldine Brain Siks, author of Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children, is one of the founders in the mid-20th century creative drama movement (perhaps “movement” is a term of too much import; it’s not like there’s a logo or catch phrase for easy t-shirt recognition!). She was a student of Winifred Ward, and the Seattle Children’s Theatre honored her (along with Agnes Haaga) as their “godmother.” Her Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children is a classic textbook for students of creative drama. Some parts of it are what we in the 21st Century would call “evergreen content.” Other sections of the text haven’t aged as well; some cultural sensibilities of the 1950s are now mostly anachronisms. (You can borrow the 1958 version of the book from archive.org; many public library systems also have a copy in circulation.)

Siks’ tone is overwhelmingly pleasant; she and the teachers she describes are as utterly delighted with the children as they are with their teaching. They do seem genuine, but they left me with the feeling that all of the teachers saw themselves as Mary Poppins…practically perfect in every way. On the one hand, it’s great that they have that confidence; on the other, maybe they’re suppressing the challenging aspects of their classes?

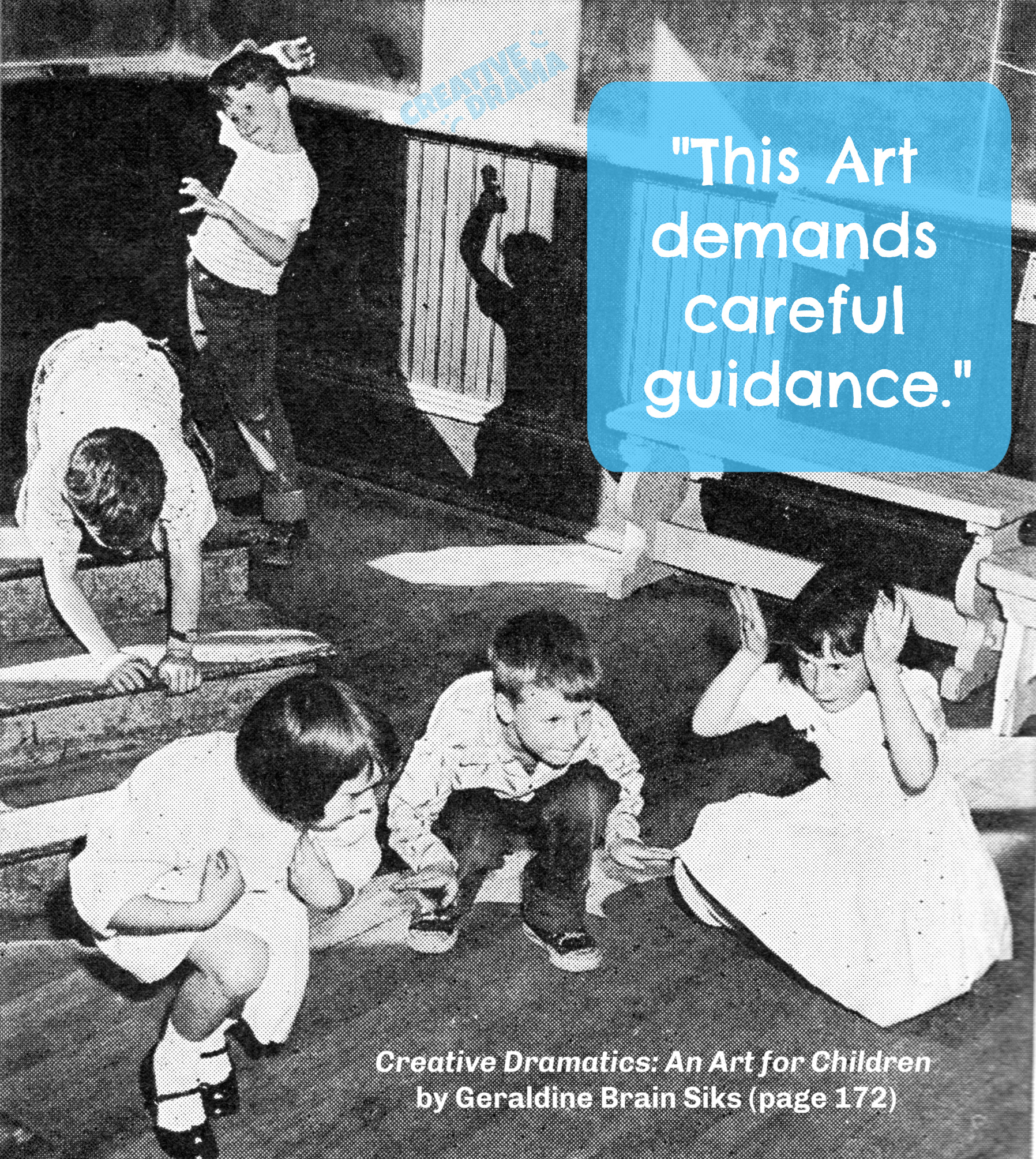

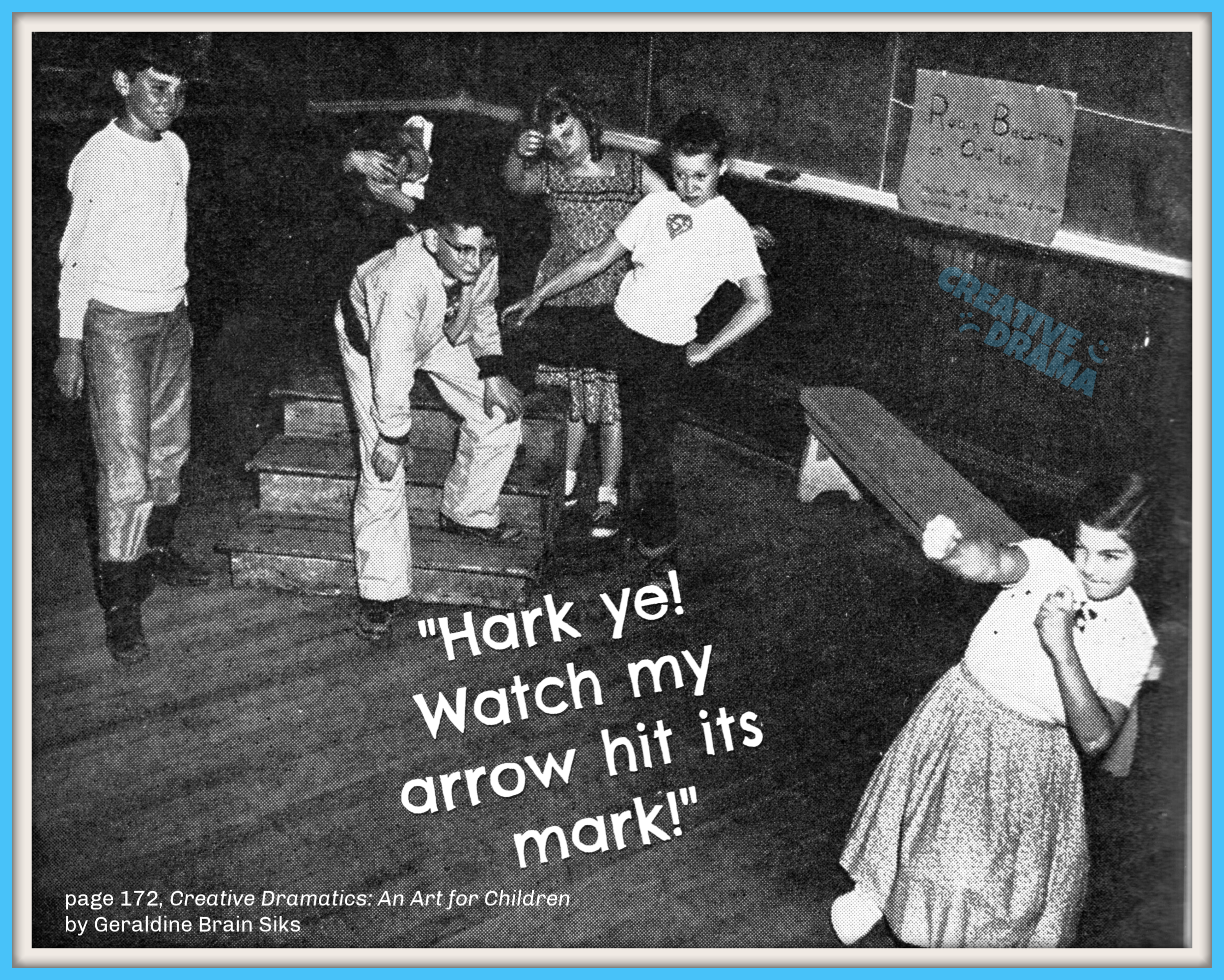

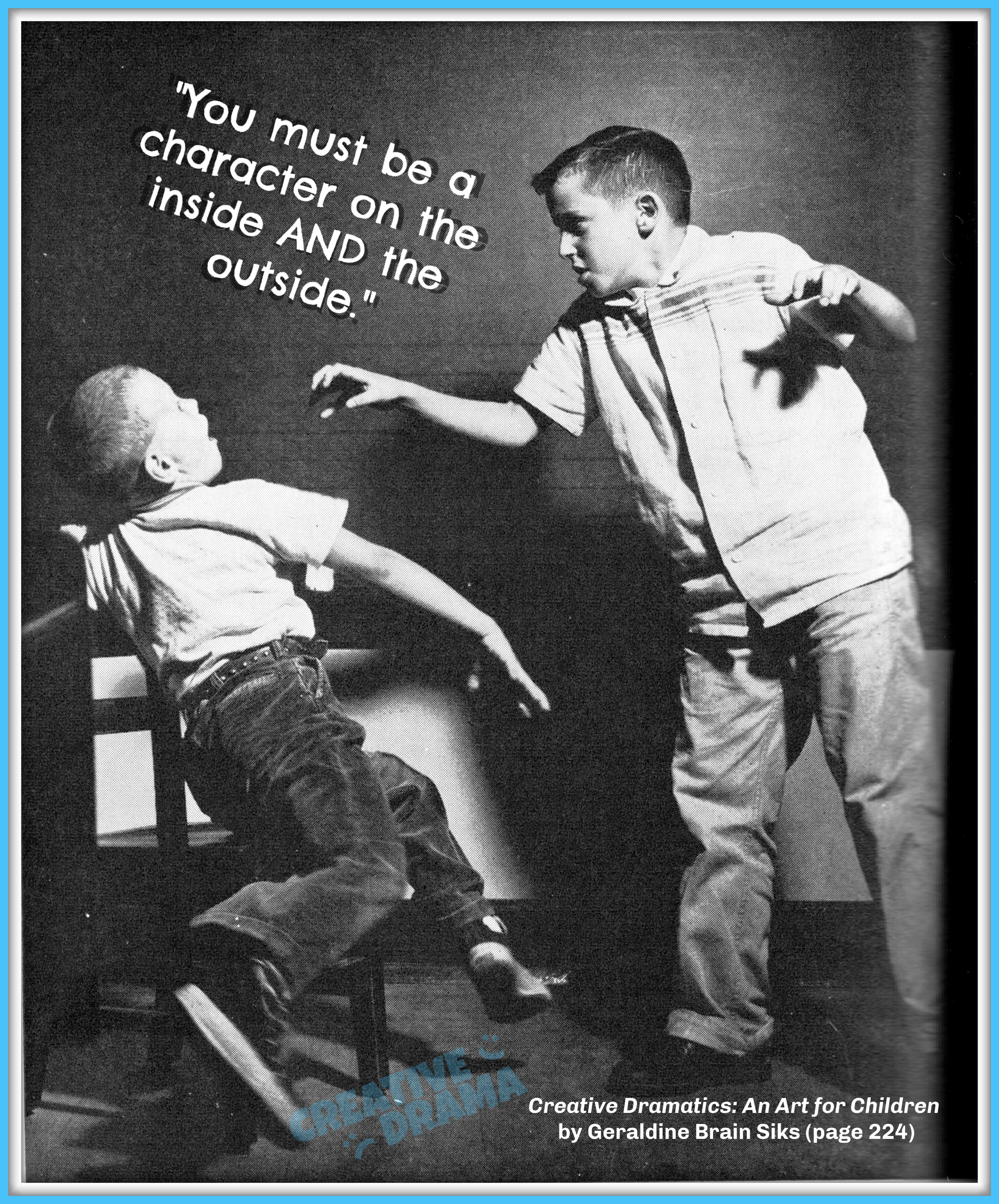

The photographs included in the book capture some great moments in creative drama classes; the expressions on the participants’ faces, and the physicality in their movements, show a total commitment to the stories they’re enacting.

Because Siks designed the book to help teachers learn how to integrate creative drama into their classrooms, it’s organized like a college text. There are questions and exercises for students at the end of each chapter, and many of them are useful for philosophical as well as practical teaching considerations. However, I’d add this caveat to each set of student tasks:

How would YOU adapt these ideas for YOUR students today?

Chapters 1-3: A CHILD AND HIS ART; CREATIVE IMAGINATION & THE ART OF DRAMA

The educational philosophy Siks outlines in the first chapters of Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children – regarding art and creativity in particular – is on solid footing that holds up even today:

“A child needs beauty and love every bit as much as he needs food and exercise. He needs quiet just as he needs laughter and shouting. He needs to be alone just as he needs to be with others. He needs to work as well as to play. All components of growth are equally important if he is to develop a wholeness of personality. For a child to live is quite a different thing than for him to exist. He needs to be guided in his growing so he reaches for his best. He needs to find his way to enjoy and contribute to the world in which he lives.”

Siks details the characteristics of creative drama practice, which still hold true today:

- No scripts

- No Technical Aids (costumes, sets, props, lighting)

- All of these can happen via the participants’ imaginations. Siks provides a great example of students’ creating wonderful costumes with their minds with this 11-year-old’s description of her queen character’s attire:

- “I wore a long golden dress and a cape of scarlet satin with white ostrich plumes over it. My crown was a band of gold with a big diamond right in front.” (20)

- No Audience

And the requirements:

- A group of children

- A qualified leader

- A space large enough for children to move about freely

- An idea from which to create

The imagination journey Siks details in “Creative Imagination,” Chapter 2 of Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children demonstrates the magic that can happen when a teacher is willing to “play along” with her students. Carol, the girl whose toy giraffe Blue Queenie helps start the traveling, seems to have picked up all of the elements required for an imagination journey. The teacher allows Carol to take the lead, and provides opportunities for other students to contribute throughout the experience. The resulting class “Trip to Fairyland” is an exciting and engaging exemplar of a creative drama session.

In Chapter 3, Siks explains the fundamental elements of drama and dramatic terms for readers. She uses the cultural touchstone of Cinderella to illustrate her examples, and she’s very thorough. A teacher new to theatre and creative drama can easily learn the basics through this chapter. Instructors who are familiar with the elements of drama can pick up tips on how to convey them to children.

Chapter 4: A CREATIVE LEADER

“A Creative Leader,” Chapter 4 of Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children, is a mixture of useful pieces of advice for teachers and a few cringe-worthy ideas. When Siks starts listing the qualities of a creative leader, she actually references Mary Poppins as a prime example of the power of imagination.

I LOVE these two evergreen sentiments:

- “When a leader is enthusiastic enough to fire children’s creative spirits, something significant always happens.” (125)

- “A leader’s righteous discontent keeps her striving to strengthen her guidance and her development as a person.” (129)

However, there are also statements like this:

“If a leader has a fresh clean, attractive appearance, and wears little touches of beauty and color, she soon find children coming to class looking fresh and clean. She finds boys combing their hair and taking an interest in the way they look. It is not uncommon to find girls wearing flowers and bright colors just like those the teacher wears.”

This is a good example of the Siks’ Pleasantville mindset: she seems positive that all children have access to clean clothes that are in good condition, that they have the same aesthetic as their teacher, and that they are able to discern the implicit social cues that come with wearing particular clothes.

The section on “Guiding Children with Strong Needs” (143-144) covers “the shy child” and “the child with aggressive behavior patterns.” Siks’ description of the latter’s difficulties includes references to “taking turns” and being able to participate in “minor roles,” which sound like challenges most drama teachers today would love to overcome!

Chapter 5: MATERIAL FOR CREATIVE DRAMATICS

Siks shows how a teacher might approach a story for use in a creative drama class in Chapter 5: “Material for Creative Dramatics.” She provides a detailed example of an analysis of the Brothers Grimm story “A Tailor and a Bear,” including the dramatic elements, the appeal of the story to children, and the basic needs of children that playing the story might meet. An exercise like this would be useful for any text teachers are contemplating for use in creative drama. For today’s instructors, I’d suggest adding “challenges of the story” and “adaptations for my students” sections.

You may find that the activities, poems, and stories suggested in this chapter, as well as later sections for particular age groups, need to be moved to younger kids than Siks indicates. Today’s children have usually had ample exposure to sophisticated storytelling. Being able to watch TV shows like A Series of Unfortunate Events, movies such as Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse, and read the children’s novels of Neil Gaiman means that 7- to 11-year-olds aren’t going to stand for works that talk down to them. Even shows for preschoolers like Sesame Street, with its rapid-fire segments, and the books of authors like Jon Scieszka, Mo Willems, and Doreen Cronin, have advanced the ability of children to appreciate humor and metafictional techniques.

My suggestion is to follow Siks’ guidelines, but YOU should select your material to use with participants. (Not sure where to start looking? I have lists of Resources for Creative Drama and Children’s Picture Books that have some more recent examples to get you started!) As Siks says herself: “(A creative leader) searches for stories and ideas that are “just right” for a specific group of children instead of using an experience that another leader has found to be right for her group.” (124)

Chapter 6: HOW TO GUIDE CHILDREN TO CREATE DRAMA

Siks suggests starting a creative drama session by “motivating children into a specific mood.” Today’s teachers call this the “anticipatory set” or sometimes “a hook.” All three work the same way: fire up the students’ brains to get them excited about what’s coming next. Siks lists several approaches to motivation, including a “searching question”: the equivalent of a divergent (open-ended) question with many right answers and fewer “wrong” ones. Her explanation is very clear, and teachers can easily adapt her examples of divergent questions to their own classrooms.

The tips Siks provides for “Motivating: Guiding Children” and “Sharing” and “Telling a Story” have great value, although some of the illustrations of the concepts suffer from age. For example, she often references the Christmas story, which would only work for teachers at Christian or Sunday schools today.

The “Planning” section is a little overly detailed with character questions for the participants. It might be difficult for kids to do all the ahead-of-time planning that Siks sets forth for them. They would probably prefer to play the story with minimal planning, then go back and consider some of the in-depth questions.

It seems like most of Siks’ classrooms have had a large number of students, and she often splits the class in half, creating audiences for the performers as they take turns. Siks asks students to consider the playing space as if they are performing for an audience – “Who sees how we might make a more interesting ‘stage picture’ when we play this scene?’ – and wants to make sure every character “feels free to move.” (220) She also gives reasons why a leader might join in with the playing, which are still valid today.

“Praising and Evaluating” – Siks believes very strongly that “A few words of praise work wonders with a child.” Since 1959, there’s been a lot of literature on the subject of praising children effectively, both in the home and the classroom. Parents and teachers swim in advice regarding “how” and “when” and “to what degree” they should praise children, and it can leave us with the impression that humans had been doling out praise in the wrong way for centuries. However, most of Siks’ examples praise ideas and specific actions/choices the children are making, rather than the students themselves. She doesn’t use the word “best,” she says things are “good” or “wonderful.”

She says, “A leader uses care in giving every child individual ‘moments of glory,’ and a few children recognition which lasts longer than a glorious moment.” (235)

CHAPTERS 7, 8, and 9

The last section of Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children dedicates a chapter to each of three different age groups (“little children;” seven- and eight-year-olds; and nine-, ten-, and eleven-year-olds. In each chapter, Siks provides an anecdotal example of a creative drama session; each lesson goes perfectly. She then explains for the age group:

- What the children are like

- Their interests

- How to introduce creative dramatics to them

- How to guide them in dramatic experiences

She also places creative dramatics in school context, providing ways to work it into various curriculums, and in community or religious education programs.

I mentioned earlier that some of Siks’ suggestions might need adjusting for your students; keep that in mind while reading these chapters. Siks states in Chapter Eight: “Experiences for little children are selected from material based on their interests in the real world. Experiences for 7- and 8-year-olds are selected from material based on their interests in the real world and the world of wonderland and faraway places” (315). However, you may find that your 5-7-year-old participants are ready for some “wonderland” as well.

Chapter 7: CREATIVE DRAMATICS WITH LITTLE CHILDREN

The “little children” in this chapter are 4-6 years old; Siks advises starting with activities like rhythmic movement, pantomime, music, or finger plays to get participants involved immediately.

Siks also wants teachers to schedule sessions for 15-20 minutes several times a week rather than an hour once a week. This accommodates the attention spans of kindergarten and first grade students.

Chapter 8: CREATIVE DRAMATICS WITH SEVEN- AND EIGHT-YEAR-OLDS

Siks uses an extracurricular creative drama class for the opening of Chapter 8. The students enact dreams simultaneously to music, and the teacher uses some participants’ dreams for a group pantomime and imagination journey.

After playing with the story, “How the Hen Got her Speckles,” children wrote letters to the King from the perspective of the hen. This sort of arts-integrated activity still happens in classrooms today, and there have been a lot of advancements in methodology since the 1950s. Check out these books on integrating drama into the curriculum.

The ideas for “Rhythmic Movement and Pantomime” (366-367) have not aged the way that some other activities in Creative Drama: An Art for Children have. Outdoor activities, the Olympics, seasons, music, and adventures are all familiar subjects for many of today’s students. The specific examples Siks provides as prompts will likely need tweaking – instead of traditional marching band instruments for an imagined music performance, you may want to suggest rock band ones, or a turntable/beatbox for hip-hop.

Chapter 9: CREATIVE DRAMATICS WITH NINE-, TEN-, AND ELEVEN-YEAR-OLDS

Chapter 9 begins with a student-devised play in which the students from the creative drama class have a reunion ten years in the future at King Cole’s castle (the King is also a former classmate!). It’s mostly “telling,” rather than “showing,” but the 11-year-old author seemed to incorporate all of her classmates’ aspirations for careers into the piece. (SPOILER ALERT: They are all incredibly successful in their chosen careers!) One of the exchanges in the piece is straight out of a 1950s sitcom:

MARJORIE: By the way, maybe Tom didn’t tell you that I’m HIS WIFE?

KING: I guess he wanted you to tell me.

One of the exemplar sessions Siks shares in Chapter Nine has students playing the story of Pandora from Greek mythology. She smoothly details the process of creating – from a conceptual discussion about the evils of the world to a two-scene performance – and provides quotes from the participants as well as the teacher. What I found particularly interesting about her anecdotal account was the footnote at the beginning:

“This is a composite condensed account, from students’ (college students) observation reports, of a class at the Seattle Public Library under the sponsorship of the School of Drama of the University of Washington.”

So perhaps Siks was polishing and perfecting the classes for inclusion in Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children so that they represented an ideal creative drama session.

A hypothetical situation in the Questions and Activities sections for Chapter 9 starts, “You have just arrived in Rainbow Valley…” and goes on to report that “the children are enthusiastic about creative dramatics; the parents curious” (401) Even though I know there are actual places named Rainbow Valley in the U.S., I still giggled at the thought – of course the Mary Poppinses of Siks’ imagination get teaching jobs in Rainbow Valley!

APPENDICES

Siks provides plenty of resources for teachers in the appendices. If you’re interested in the history of education/teaching theatre, you’ll find some interesting titles in the Bibliography. The “Material for Creative Dramatics” in Appendix B is arranged by age, then by subject, and includes explanations of why children enjoy the pieces. Some of the pieces are classic folk and fairy tales; you can likely find a recent storybook version or revision – like Jon Scieszka’s The True Story of the Three Little Pigs – by A. Wolf – that will work well for your students. There are also many pieces of music from a book series called The American Singer.

A word of caution: don’t assume that material Siks recommends is appropriate for your students because her suggestions skew younger or she was writing in what many think was a more innocent time. There are pieces of children’s literature and folk songs that contain content which was okay in the 1950s; that doesn’t mean it’s acceptable by your or your school’s standards today.

CONCLUSION

Creative Dramatics: An Art for Children is a foundational text in theatre education; anyone doing creative drama with preschool or elementary students should read it. Yes, you’ll need to keep the cultural influences of Siks’ time period in mind, but much of the book is both useful and adaptable.